What is commodity? A commodity is an asset that is interchangeable with goods or services of similar market value.

What is an asset? An Asset is a resource with value in the market.

A Market is a system where resources can be transferred by Voluntary Exchange. Voluntary Exchange is the most common form where one party (a seller) engages in transactions willingly with any other party (a buyer). Buyers and sellers exchange goods or services for money, or sometimes for other goods and services (barter). As such the value of a given resource (such as sacred land) might not be obvious to all parties involved in the exchange.

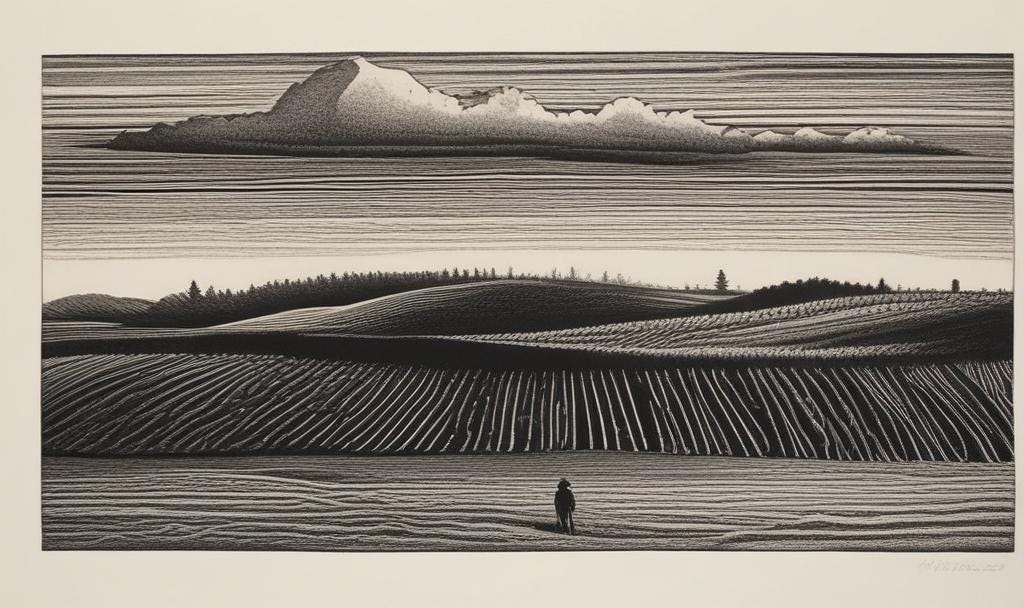

A resource that is not an asset might have value for non-market actors. Land for instance, has value for non-human agents such as those found in a natural ecosystem.

Land is not capital for several reasons:

Land is not commodity for several reasons:

Fixed Supply

Land, unlike capital, has a fixed supply. While commodities can be produced or extracted in varying quantities, the total supply of land is fixed. The earth's surface area is not expandable; thus, land does not have the elastic supply that many commodities possess. This fixed supply means that land prices are driven more by demand rather than by fluctuations in production. Controlling demand will not affect production, unlike a commodity which is a resource whose supply is elastic, mutable, or variable.

Economic Rent

Land generates economic rent, which is the payment to a factor of production in excess of what is needed to bring that factor into production. This rent arises from the land's inherent value (location, natural resources), not from what's built on it such as improvements or labor (which would be capital enhancements). According to Georgists, this economic rent should belong to the community since it's society that creates the demand for land, not the individual landowner.

Efficiency

Treating land as capital leads to inefficiencies. When land value increases due to community growth or public improvements (like infrastructure), landowners benefit without contributing anything. This, Georgists argue, leads to speculative land holding where land is bought not for use, but to hold for rising value, which can inhibit development and access to land for others.

Non-fungibility

Commodities are fungible, meaning one unit can be exchanged for another without affecting the buyer's satisfaction. Land, however, lacks this characteristic due to its unique attributes. Each piece of land is unique in terms of location, size, topography, natural resources, zoning regulations, and ability to sustain living systems within it. Furthermore, the value of land is significantly influenced by its location, which is inherently fixed and cannot be changed. This contrasts with commodities, whose value is more about quantity and quality rather than where they are. A plot of land in one area cannot simply be swapped with another plot of equal size elsewhere without considering location, zoning, access, obligations etc.

Non-subtractible

Unlike many commodities which can be consumed or depleted (like oil or food), land remains. Land is not a subtractible resource, which means that it is a durable resource that doesn't get used up (subtracted) in the production process but can change in value based on what's done with it or around it.

Obligations

Land comes with a complex web of rights, zoning laws, cultural significance, and historical ownership, which aren't typically considerations for commodities. These factors affect how land can be used, sold, or developed.

Taxation Policy

A core tenet of Georgism is the Land Value Tax (LVT), which would be levied on the unimproved value of land. By taxing land rather than capital improvements, Georgists aim to encourage the productive use of land and discourage land speculation. This taxation policy reflects the principle that the benefits derived from land should return to the community.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while land shares some economic attributes with commodities (such as being a factor of production), its unique properties, particularly its fixed location and supply, make it distinct in economic analysis. This distinction is crucial in discussions about land value taxation, urban planning, and economic theories like Georgism. By distinguishing land from capital, we can address issues of economic inequality, inefficiencies in land use, and the unearned increment in land values. This philosophy advocates for recognizing land as a distinct factor of production that belongs, in its natural state, to all members of society equally.