Coulda Shoulda Woulda: How "Could" and "Can" Make You Responsible

How modal verbs play a role in responsibility-attribution

✴️ Can, Could, and Should’ve Known Better: The Strange Modal World of Responsibility

By Vynn, June 2025

Can Jones be blamed for not saving the cat? Could he have done otherwise? Did he even know the cat was there? Welcome to the linguistic-jurisprudential funhouse where modal verbs (“can,” “could”) quietly steer the ship of responsibility—and sometimes straight into the rocks.

If you thought “can” just meant “is able to,” I regret to inform you that you're already in too deep. The humble modal auxiliary turns out to be the key to blame, praise, moral judgment, and possibly your next parking ticket appeal.

Let’s take a tour of how different frameworks interpret “can” and “could,” and how each interpretation subtly rewires our sense of whether someone’s responsible for what they did—or failed to do.

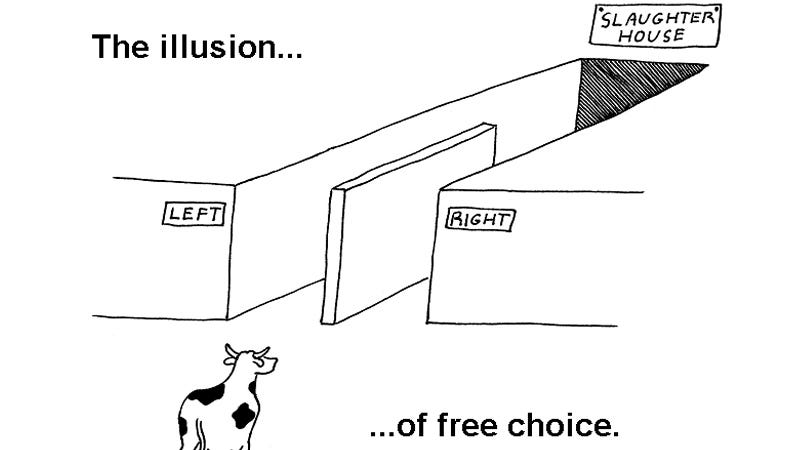

🧠 1. Compatibilists: You Can... If You Wanted To

Our first stop is the Compatibilists—philosophers who believe free will and determinism can live happily ever after. For them:

“Jones can do otherwise”

means: If Jones had wanted to, nothing would have stopped him.

So “can” here is more like coulda, woulda — you could have done otherwise, in the sense that no one tied your hands. But your desires? Those were already preloaded by the universe.

Responsibility? Yes, if you acted voluntarily, even if you were determined to do so. (Freedom-lite™)

🔮 2. Libertarians: You Really Could Have

These folks aren’t political—at least not in this context. Libertarian free will advocates take “could have done otherwise” literally. No, seriously.

“Jones could have done otherwise”

means: Even with the exact same brain, weather, and horoscope, he might’ve acted differently.

This is deep metaphysical possibility. So unless that’s available, Jones is off the hook. Sorry, determinists.

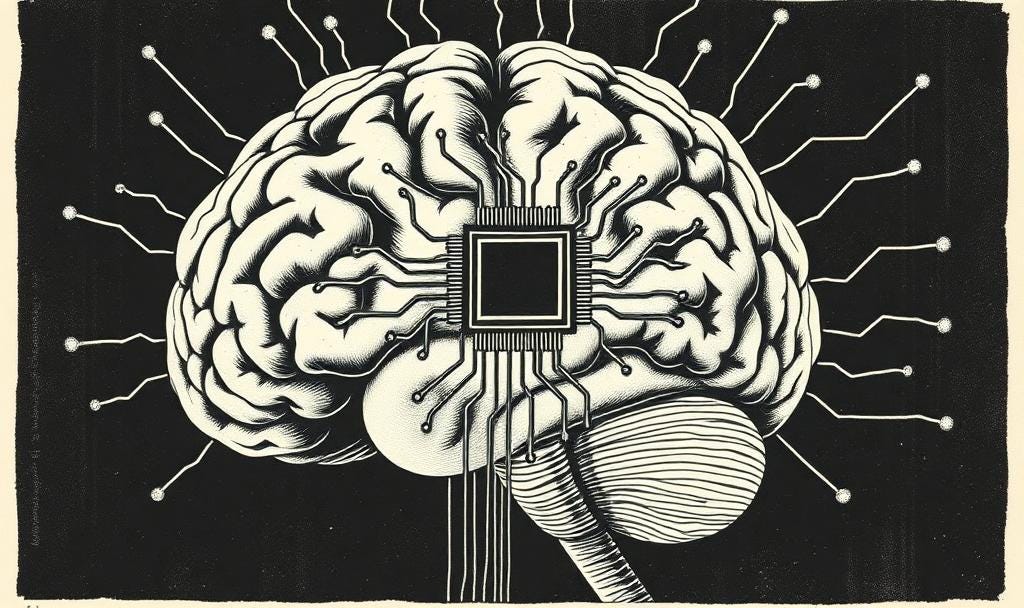

🔧 3. Frankfurt Fans: “Could” Doesn’t Even Matter

Frankfurt-style philosophers say: Forget about “could”! Suppose a secret brain chip would have stopped Jones if he tried to disobey—but he doesn’t even try.

He acts freely, even though he couldn’t have done otherwise. Why? Because what matters is that he acted for reasons he endorsed.

Responsibility? Yes—even if the alternate path was never really open. Modal freedom is overrated.

⚖️ 4. The Law: “Could a Reasonable Person Have...?”

The legal system, as always, likes its modals dressed in robes and powdered wigs. In tort and criminal law:

“Can” = Capacity (mental, physical, situational)

“Could” = Foreseeability / Preventability

“Could a reasonable person have avoided this?”

means: Would a jury of suburbanites think you should’ve known better?

Responsibility here rests on objective standards, not just your inner Hamlet monologue.

🧒 5. Developmental Psych: “Can They Wrong?”

Here, “can” means cognitive maturity. The six-year-old who draws on the wall can hold a crayon, but can they grasp moral consequences?

Responsibility gets parsed through empathy, impulse control, and prefrontal cortex development. In other words: Maybe give the kid a break.

😳 6. Situationism: “Can” Is a Trap

Situationists point out that most of us overestimate agency. Just because someone “could have said no” doesn’t mean they realistically could under pressure, fear, social constraints.

This is the “easy to say from the outside” perspective. In practice, situational forces often limit what people can realistically do—even when they have the physical or legal freedom.

Responsibility? Take it with a grain of Milgram.

🗣️ 7. Pragmatics: “Could” as Code for “Should’ve”

Now we’re into language games.

“He could have helped.”

is often not about possibility at all—it’s a moral jab.

This is “can” as an illocutionary act—a fancy way of saying you’re blaming someone while pretending not to.

🔭 Modal Logic Interlude (Optional Side Quest)

For those who want to wear a logic cape:

◇φ = “It is possible that φ”

[Ag sstit: φ] = “Agent sees to it that φ”

So “Jones can save the cat” becomes:

◇[Jones sstit: Saved(Cat)]

And “Jones could have done otherwise”?

◇[Jones sstit: ¬Saved(Cat)]

The moment you add epistemic logic, things get wild. Now Jones must also know (or be able to know) the consequences of his actions. If he couldn’t have known the cat was on the roof? Maybe cut him some slack.

🔭 Modal Logic Interlude: Now Featuring Knowledge (and Blame)

Okay, let’s get technical for a moment—but in a fun, responsibility-pinning kind of way. Philosophers and logicians use modal logic to formalize statements like “Jones can save the cat” or “Jones could have done otherwise,” but with symbols that look like they belong in an escape room. The core tool here is the ◇ (diamond) for possibility and □ (box) for necessity. In agentive logic—like STIT (short for “Seeing To It That”)—we say [Jones sstit: φ] to mean “Jones sees to it that φ occurs.” So “Jones can save the cat” becomes:

◇[Jones sstit: Saved(Cat)] — there’s at least one timeline where Jones chooses to bring about a feline rescue.

But here's where it gets spicy. Responsibility isn't just about whether Jones can save the cat. He also needs to know what’s going on. Enter epistemic logic, where K_Jones(φ) means “Jones knows that φ.” Now we’re in the realm of epistemic STIT: if Jones doesn’t know (or couldn’t possibly have known) that the cat is in danger—or that he had a ladder nearby—can we really blame him? A robust account of moral responsibility needs three key modal conditions:

Ability — ◇[Jones sstit: φ]

Epistemic Access — K_Jones(φ ∧ Consequences)

Knowability of Options — ◇K_Jones(φ) ∧ ◇K_Jones(AvailableActions)

In plain English: Jones is only fully blameworthy if he could have acted otherwise, knew what he was doing, and knew (or could have known) what would happen if he did it. If he lacked that knowledge—and couldn’t even have reasonably acquired it—we might shift from moral responsibility to tragic accident, or at worst, negligence if he could have known but didn’t bother to check. In short: if modal logic is the machinery of responsibility, epistemic logic is the conscience module.

🎯 Why It All Matters

So what?

Because every time we say someone “could have” done something—voted, intervened, spoken up—we’re implicitly relying on a framework that makes different assumptions about freedom, knowledge, control, and context.

If you believe only in metaphysical alternatives, few people are responsible for anything.

If you’re a compatibilist, most people are—as long as they weren’t coerced.

If you’re a judge, you want to know whether they knew or should’ve known.

And if you're a teacher trying to explain to a student why turning in their assignment late was avoidable, you'd better first specify which modal universe you're inhabiting.

🧁 Closing Thought

So the next time you hear someone say, “They could have acted differently,” ask yourself:

Could they really?

Could they have known?

Could they have believed otherwise?

Could you have done better in their shoes?

Turns out, “could” isn’t just about possibility—it’s the grammar of judgment itself.

If you enjoyed this modal adventure, subscribe for more responsible reasoning, blameworthy metaphors, and philosophically-charged linguistics every week. 🧠📝